Serbian Medieval History

Serbian Medieval Royal Attire

By Tanja Vuleta, 1998

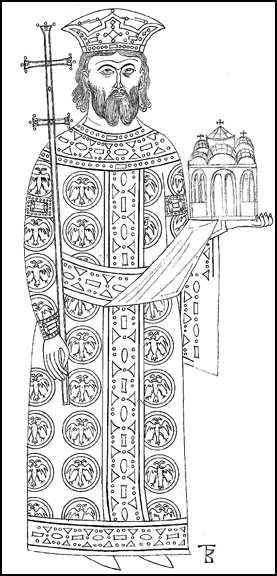

Serbian rulers' ceremonial costume emerged from its Byzantine counterpart at the very moment when Serbian rulers chose to get close to Byzantium, politically as well as in matters of religion. That costume clearly shows the manner in which governmental power was comprehended and considered at the time, while simultaneously being filled with profound religious meaning.

King Mihailo (King of Zeta)

Prince Miroslav

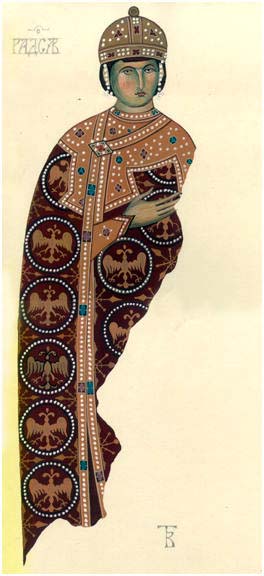

King Radoslav

King Uros I and Junior King Dragutin

Queen Jelena and Prince Milutin

Young Queen Katelina

Queen Katelina

King Milutin

Queen Simonida

Queen Jelena

Queen Jelena and Junior King Uros V

King Stefan Decanski

King Uros V

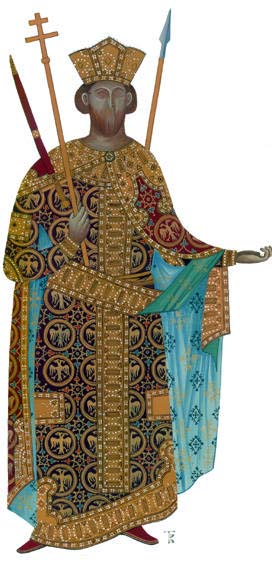

Emperor Dusan

Empress Jelena

Empress Jelena

King Vukasin (posthumous portrayal) and King Marko

Prince Lazar

Stefan and Vuk Lazarevic

Princess Milica

Prince Lazar (posthumous portrayal)

Princess Milica

Despot Stefan Lazarevic

Despot Stefan Lazarevic

Prince Lazar

Others

More Information

BLAGO Content

While the content of the BLAGO Fund collections is free to use, there are also some restrictions on commercial use and proper attribution of the material. Follow the links below for more information.

> BLAGO Collections License

> Image Request

BLAGO Fund also accepts the contribution of material. Please contact us with any material you wish to publish on our website.

Contact

BLAGO Fund, Inc.

PO Box 60524

Palo Alto, CA 94306

USA

info@blagofund.org